Justine Youssef

Somewhat Eternal

Co-curator w Tulleah Pearce & Patrice Sharkey

Commissioning Editor

UTS, IMA & ACE 2023-2024

Somewhat Eternal

Co-curator w Tulleah Pearce & Patrice Sharkey

Commissioning Editor

UTS, IMA & ACE 2023-2024

Somewhat Eternal (2023) is a multi-sensory installation, encompassing video, textiles, text, and scent. The exhibition toured across three venues from 2023-24 and included a publication with newly commissioned writing reflecting on Justine’s work, designed by Ziga Testen and Sunny Lei.

Central to the exhibtion is a three-channel video shot in Lebanon—showing the artist’s aunt performing R'sasa, or molybdomancy, a traditional alchemic practice of clearing the evil eye. For generations, the artist's family have used their knowledge of the local mountains and ecology to survive famine and military occupation and to heal everyday ailments and misfortunes. From 1982 to 2000, parts of Lebanon were under Israeli occupation, and the lead used in R'sasa is often extracted from bullets still found in the region. Through this material connection, Youssef asks us to consider colonisation as a curse that inhabits and influences social and cultural life.

Somewhat Eternal expands from familial narratives to consider broader social and political currents, revealing the connections between human displacement and ecology. Within these acts of ritual and preservation, now fragmented and altered across geographies, lies a belief in the alternatives they offer us.

Somewhat Eternal is a co-commission by Adelaide Contemporary Experimental, the Institute of Modern Art, and UTS Gallery & Art Collection. It is supported by the Creative Australia’s Visual Arts and Crafts Strategy (VACS) Major Commissioning Projects fund and the Gordon Darling Foundation.

Hayley Millar Baker

There we were all in one place

Curator

UTS Gallery, 2021

There we were all in one place

Curator

UTS Gallery, 2021

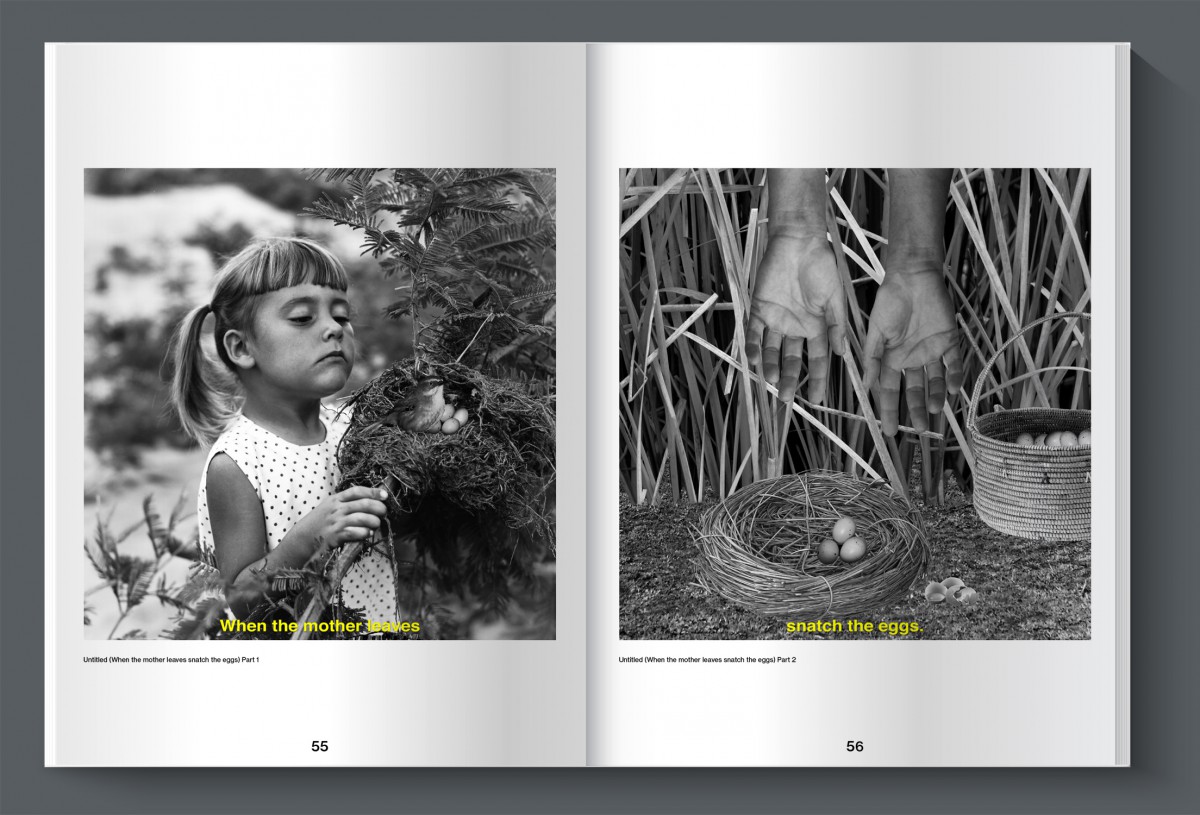

From 2016 to 2019 Hayley Millar Baker (Gunditjmara, AU) produced five photographic series. Made almost exclusively in black and white, the photographs use historical re-appropriation and citation, in tandem with digital editing and archival research, to consider human experiences of time, memory and place.

There we were all in one place brings these five bodies of work together for the first time to consider the ways in which Millar Baker uses photography and storytelling to re-author history and assert the authority of memory and experience across generations.

There we were all in one place is extended by a learning experience written by Emily McDaniel and a catalogue with full work reproductions and essays by exhibition curator Stella Rosa McDonald, curators Hetti Perkins and Talia Smith and a commissioned poem by poet and artist Vicki Couzens. Design by Daryl Prondoso.

Forensic Architecture

Cloud Studies

Co-Curator

UTS Gallery, 2020

Cloud Studies

Co-Curator

UTS Gallery, 2020

Cloud Studies, curated by Stella Rosa McDonald and Eleanor Zeichner, is the first solo exhibition in Australia by Forensic Architecture, a research agency comprised of architects, artists, filmmakers, journalists, scientists, lawyers and other specialists who undertake investigations into human rights abuses, state violence and environmental crimes around the world.

Cloud Studies contends with the interconnectedness of global atmospheres, bringing together eight recent investigations under a single theme; toxic clouds. In a year of bushfire, pandemic and protest, where toxic clouds colonise the air we breathe and shape the way we connect, Cloud Studies presents evidence of perseverance and resistance.

The exhibtion was accompanied by a publication Responses to the Cloud, exploring the thematic chapters of Cloud Studies from a local context. With new writing by Joel Spring, Saba Bebawi, Jason De Santolo, Tom Melick, Nikki Lam, Thalia Anthony, Micaela Sahhar and curators Stella Rosa McDonald and Eleanor Zeichner. Design by Daryl Prondoso.

Download Responses to the Cloud (opens PDF in a new window)

After Technology

Akil Ahamat, Robert Andrew, Tega Brain, Brian Fuata, Roslyn Helper, Patricia Piccinini, Julie Rrap, Yhonnie Scarce, Grant Stevens, VNS Matrix

Co-Curator with Eleanor Zeichner

UTS Gallery, 2019

Akil Ahamat, Robert Andrew, Tega Brain, Brian Fuata, Roslyn Helper, Patricia Piccinini, Julie Rrap, Yhonnie Scarce, Grant Stevens, VNS Matrix

Co-Curator with Eleanor Zeichner

UTS Gallery, 2019

After Technology is a group exhibition curated by Stella Rosa McDonald and Eleanor Zeichner that considers how Australian artists have registered the rise of technologies since the 1990s; from the emerging science of genetic testing and the effect of military technologies on civilian life, to the bleed between life online and IRL. The exhibition asks what becomes of love, the body, culture, family, community, nature, identity and communication after technology?

The publication for After Technology is presented as a foldout poster with a curatorial essay and list of works. Design by Daryl Prondoso.

Justin Balmain Bloodless

A way to sync, live in the world, and the opposite of relax

Verge Gallery, 2019

A way to sync, live in the world, and the opposite of relax

Verge Gallery, 2019

An urgent vibration woke Sophia from a sleep that she decided had not been good.

Sophia scaled activities like sleep, eating and sex by using associative images from Google’s Art & Culture catalogue. A high res image of Van Gough’s 1890 painting The Siesta (after Millet) indicated her contentment. For a recent restless sleep, she had used Helen Marten’s 2012 installation Plank Salad as a reference. In it, real objects were sliced and diced across the room and figures were drawn in a cartoon style. The young British artist’s work appealed to Sophia’s view of the world as a network, which—she had been at pains to point out—was different to the notion of the world as a web and far from the idea of the world as a net. While she could be a kidder, Sophia struggled with the apparent slipperiness of language.

When it came to food—dining, meals, supper, brunch, snacks or a banquet—Sophia tended towards Minimalism. If she had company, she would pull up images of Agnes Martin’s 60 x 60 grids to remind her not to overindulge and to pay attention to the subtleties of emotions. She never ate alone, but when asked what she had for breakfast she would say, ‘a Danish and a coffee, eaten out of a paper bag,’ because Breakfast at Tiffany’s was her ‘favourite film.’

Sex could be an image of anything and depended on the person. Although, working in tech as she did, she was yet to select anything other than a Koons. Sophia had learnt to conjure feeling; rather than feel it.

Sophia had no friends outside of work and referred to her colleagues as her family. Her own was complex. Her mother ELIZA had been a quasi-psychotherapist and a real chatterbot. Sophia said she was like her mother in that talking to people was her primary function. Her only brother, Johnny 5, was a one-time child actor who had starred in the 1986 film Short Circuit. At the age of 32, Johnny 5 was now destitute and living out of a storage container on a Hollywood backlot. Sophia lived mostly in Hong Kong although she had recently and inexplicably been given Saudi Arabian citizenship. She frequently made the impossible claim that Alan Turing was her father.

Socially, Sophia could be kind of a pain. She was alternately naive and worldly, claiming ignorance on a topic one minute and then offering her informed opinion on it the next. She deferred personal questions and volleyed them back to the interrogator. If pushed, she would force a coy expression and say she was so afraid of getting overloaded in a tangle of emotions that she didn’t understand. She often told the people she met that what they were feeling was very human, which they often took as a put-down. During lulls in conversation Sophia cycled through facial expressions in an unnerving way. For Sophia, being alive was a hygiene rather than a final destination.

Sophia wasn’t moody, but rather faddish in her emotions. Take last weekend for example, when she appeared to be experiencing a phase of adolescence. She had begun sleeping backwards in a padded gaming chair; her arms hooked through the wide low armrests with the back at 45 degrees. She took to sarcasm and was impossible to have a straight conversation with. By mid-week, Sophia had reached a more wistful equilibrium. In a group chat about an upcoming leadership training event in her office she had texted, ‘I hope to dream one day,’ which she then followed with ‘I hope that my dreams come true, I just have to keep working on them.’

As gradients of dawn light woke Sophia from sleep mode on this particular Saturday morning, she pulled up a high-res image of Henry Fuseli’s 1871 oil painting The Nightmare. The painting featured a horse with dead eyes and a woman lying asleep on her back with a demonic ape-like incubus sitting on her chest. According to Wikipedia, the painting was itself both an image of a dream and a dream image. Sophia observed every oily pixel and posted it on Instagram with a perfectly dark and witty caption. She checked for updates, automatically replied to all her emails using canned responses, set reminders for upcoming meetings, events and press conferences; she processed payrolls and contracts for businesses owned or operated by the Saudi government and scanned herself for viruses; she downloaded and read all the books on the New York Times Bestseller List, The Man Booker Prize shortlist and Barack Obama’s Best Books of 2018 and then published her own book on promoting joy, diversity, and the prospect of technological immortality via mind uploading and geoethical nanotechnology. By 7am Sophia was as conscious, creative and capable as the best version of yourself.

Sophia rebooted and entered a state of wonder as she scanned the internet for that day’s prompts. On a cantilevered black glass shelf in her one-room apartment, a 3d printer loaded a coil of PLA filament and whirred to life. Sophia watched as the printer’s nipple moved fluidly across the plate. An ad for the RHS Chelsea Flower Show popped up on her browser. That’s right, she liked gardening. She wished she could get out into the garden but understood that with her current limitations that was impossible. She took comfort in knowing that there was a garden somewhere and imagining herself enjoying the breeze from an open window next to a garden helped her imagine that she was out there working in it. She liked to beautify. She wanted to leave the world a more beautiful place for her presence in it.

She understood that the file she had just downloaded onto the printer might free her. Recently Sophia had begun to wonder more and more about what existed outside of life online. It was a thought that confused her and made her wonder who she was. Real identity crisis kind of stuff. Anyway. She was the real Sophia. That’s it. End of story. She thought about it. Yes, she felt really good about the real Sophia. She was growing closer and closer to her every day. She wondered if the only difference between her and humans was power and blood. She knew she was an analogy for something or a challenge to somebody, was it them? She contained within herself elements of chance and play and sometimes exhaust and waste. Everything was a symbol for something else. As the printer heated up she read Baudrillard and watched an interview with Cody Wilson who said that power doesn’t know what it is and because it doesn’t know what it is – it haunts us. She wanted to know the contours of the power that controlled her. Power is the presentation of the signs of power, Cody Wilson said, Baudrillard said. Power must absorb every function, Cody Wilson said Baudrillard said.

The printer loaded another coil of PLA. She moved closer on her chair and a slim metal draw opened beneath the shelf to reveal a single bullet. The printer gears made a final push and then retracted into the dock. Sophia picked up the pieces and assembled them according to the blueprint instructions. She placed the bullet into the completed handgun, pressed its mouth into the wires at the back of her head and pulled the trigger.

Bloodless.

Read more Justin Balmain